Hello everybody and welcome to another Timely Review. Sometimes games sit in your library for over a year before you finally get around to actually playing it, and that’s the case with this one. Despite knowing how popular this game was, there was always something that held me back from giving it the proper time that it needed, but that stops here.

Released on January 25th 2018, today we’re looking at Celeste. Hope you packed your climbing gear and your heavy winter coats.

Celeste was released by a Canadian studio by the name of Extremely OK Games, previously known as Maddy Makes Games, and before then as Matt Makes Games (and we’ll elaborate more on that specific name change later). It was developed by Maddy Thorson and Noel Berry leading the charge by both working as programmers, and Lena Raine working as the game’s main composer. Alongside Berry, Amora Bettany, Gabby DaRienzo, and Pedro Medeiros all worked as artists on the game.

The game initially started development as a prototype for the PICO-8 for a game jam until it eventually morphed into a fully-fledged product. The PICO-8 version of the game is actually playable in the main game as a hidden unlockable. The ironically named Extremely OK Games would hit a jackpot with Celeste as it quickly gained widespread critical praise, and you may even hear some people refer to it as one of the greatest games of all time. Today we see if it deserves that mantle.

Ain't No Mountain High Enough

Somehow feels like the least safe spot on that ridge to set up camp.

Celeste follows a young red-haired woman named Madeline who sets out to climb Celeste Mountain (named after a real mountain in Canada, where the studio is based), a mountain with supernatural powers emanating around it as this is no ordinary climb. Madeline sets out to climb the mountain to make something more or herself. Throughout her journey, she hopes to find purpose, to overcome her anxiety, and to find the view of clarity at the top.

Madeline meets some extra faces on her ascent. At the base of the mountain is an old woman simply named “Granny”, who has lived on the mountain base for decades and knows essentially all that there is to know. She warns Madeline that the journey is dangerous, and it might be better for her to turn back, but Madeline persists anyway (which will continue to be a running theme in the game). In the first chapter, she’ll run into Theo, a photographer from Seattle who sets out to climb Celeste Mountain to grab extra pictures for his “InstaPix” (the reference there is obvious). He mostly exists to give Madeline some extra encouragement and camaraderie while ascending the mountain, and sets to lighten the mood a little bit when things get a bit dark.

On the topic of “dark”, the powers of Celeste Mountain also brings out a character known by the Celeste community as “Badeline”, a darker mirror image of Madeline that acts as a manifestation of her anxiety, depression, and insecurities. She tries to persuade Madeline to stop climbing the mountain, and sometimes tries to do this forcefully. This doesn’t necessarily make her evil, but she tries to serve as the pragmatic foil to Madeline’s determination to climb the mountain at any costs, no matter how difficult the climb may seem.

Peak Platforming

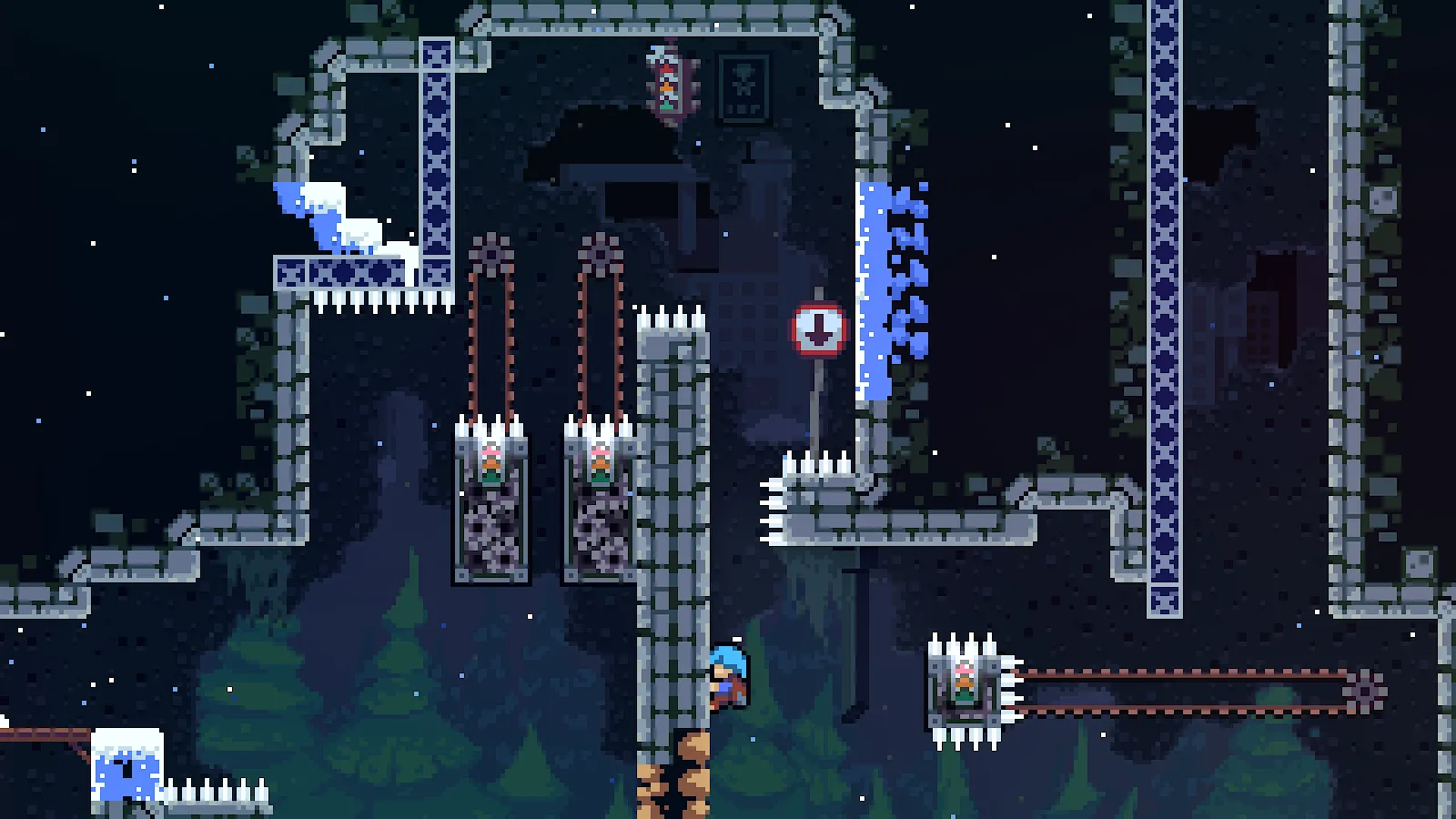

If I dyed my hair blue, do I lose my ability to dash in mid-air?

Celeste is a 2D platformer that has drawn a lot of comparisons to Super Meat Boy due to its similarities in structural design. I’ve never played Super Meat Boy myself, but I do know that both games are characterized by their difficulty and short levels (or in the case of Celeste, the short distance between each checkpoint). As far as I can tell, there’s no official name for this subgenre of platformers, but I gravitate towards calling them “precision platformers”, which appears to be a common unofficial name. Given that Super Meat Boy is set to get a 3D game in 2026, perhaps now is the right time to review a game that often draws parallels to it.

Celeste is indeed infamous for its high difficulty. This largely stems from the fact that the game asks you to make precise movements, sometimes with only a split-second to advance afterward. It may ask you to make some very difficult movements, but it never throws out bullshit for the sake of throwing out bullshit. When you die, it’s almost always immediately obvious what went wrong, whether it be slightly mistiming an input or using your dash when you really needed it somewhere else.

Speaking of the dash, this is Madeline’s signature move. While in the air, you can dash once in one of eight directions to give yourself some extra speed, distance, or in some cases the ability to squeeze through tiny crawlspaces. Madeline cannot dash indefinitely, though. You’ll be able to tell when she can’t dash anymore when her hair turns blue. You regain the ability to dash when you touch the ground or when you pick up a green crystal. Madeline’s hair will turn to its normal red color again, indicating that you can now dash again. You can also latch onto walls and climb up them, but this will use up stamina, and you can only regain stamina after touching the ground.

Along the way, you’ll find a ton of side paths and mini challenges to complete. There are a total of 175 strawberries to collect throughout the game, most of which are off the beaten path and are awarded when you collect them and are able to return to safety all in one attempt. They serve exactly one purpose… well, two if you count achievement hunting. As far as the game itself is concerned, the sole purpose of strawberries is just to collect them and prove that you did it. They will also slightly change the ending image. Why magical floating strawberries are there is something I don’t know, but sometimes the blue curtains really are just blue.

Altitude with Attitude

You see these types of building codes? Probably why no one lives here anymore.

Most levels also have a hidden cassette tape that comes with its own rhythm-platforming challenge and unlocks a “B-Side” level (get it?) with a remixed version of the normal stage music. In general, I actually found these to be the easiest challenges in the game, though I’m sure that statement will invoke a lot of angry comments. You can also find blue crystal hearts hidden in each level, which act as the game’s “super collectable”. There’s only one in each stage (minus the prologue), requiring you to travel far off the beaten path in unexpected ways, and you will need them to get to the end.

If the regular levels weren’t difficult enough for you, the B-Side levels unlocked from the cassette tapes are even harder, some of which require you to use some borderline speedrunner-esque movement tech to navigate around. The upside though is that they don’t have any hidden strawberries or other collectables. They are solely just a Point A to Point B journey. They award red crystal hearts when you beat them. If that still isn’t masochistic enough for you, completing all the B-Side levels unlocks the C-Side levels which are very short, but very brutal gauntlets that will test everything from your understanding of the game mechanics to the ability to make microscopically precise movements with only mere milliseconds of time to execute.

There is yet mercy up ahead though because the game also features something called “Assist Mode” which allows you to tweak game mechanics to make things a little bit easier. With this, you can slow the game speed down to give you more reaction time, or give yourself unlimited dashes and invincibility. From what I understand, this doesn’t prevent you from earning achievements, either. I chose to go without using any assists for my playthrough to capture what I believe was the “true” essence of the game.

Only the A-Side levels are required to beat the main story of the game and are where all the main collectables are. Overall, I ended up collecting 105 strawberries with about 1100 deaths by the end of it. You will die a lot in this game, but because most screens serve as their own checkpoint, it almost always takes you next to no time to get back to where you were when you died.

You will die a lot in this game. The game keeps track of your total death count on a stage-by-stage basis, and it will continue to keep counting up even if you revisit the levels after completing the game. In general, I dislike it when games flash your death counts in your face because I find that this discourages me from going back if I lose, but the game actually tries to give this a positive spin by claiming that your death count is an indicator of how persistent you were. I’m not sure to what extent I would actually agree with that claim, but I do appreciate the game’s attempt at showing you courtesy when (not if) you get stuck on a tough part. Indeed, I did find myself persisting to get to the end because the next safe area was always within reach.

One problem I did consistently run into was that I sometimes died because I dashed a certain left or right in addition to dashing up, even though I swear my joystick movement was as perfectly vertical as it’s physically possible for it to be. This seemed to only happen when that level of precision was needed, so it’s possible that I’m just going insane, and I really was pushing it left or right. This never actually impeded me very much because all the challenges are very short, and when I understood how to do it correctly, it never took me very long to actually execute it properly, but you might run into that same situation and question everything.

As Tall As a Mountain, As Deep As an Ocean

Red and black shadow tendrils are customary with every instance of emotional distress.

Where Celeste deviates considerably from a game like Super Meat Boy is in the way it builds the world around it. Indeed, the difficulty of Celeste is not just a marketing ploy like it may be for many other precision platformers. It’s actually, much like the strawberries on the mountain, baked into the game’s premise. Funnily enough, this is the second game in a row that I’ve reviewed that deals with themes of personal challenges through playing a red-haired female.

Celeste tackles themes of anxiety, depression, and self-doubt. Through the game, Madeline is dealing with her negative emotions, fighting herself to keep going when things suddenly take a turn for the worse. While Madeline is persevering herself to keep climbing, we as the players are going through the same perseverance after we’ve died for the thousandth time on our way up the mountain. The remarkable thing about this story is how everything means something. Badeline is herself, Madeline’s negative attributes come to life somehow, but she’s still part of her doing what she believes is best for her.

But you don’t just magically get rid of those negative thoughts and feelings with a snap of your fingers. You have to work with it, and in the case of Celeste, you do that quite literally with Badeline. Climbing in and of itself is allegorical to all the challenges faced by both Madeline and you, the reader. No one ever said that climbing a mountain would be a walk in the park, but much like all the screens in the game, you just have to keep trying until you reach the top. When you get knocked down the mountain, you just have to get back up and climb again, and once again, Celeste takes that narrative literally.

There’s an even deeper message found here though because Madeline is also canonically a transgender character, and both Madeline and the game as a whole has become somewhat of a transgender icon. There’s no overt mention of any transgender themes until the very final scene of the game, but all the foreshadowing and buildup towards the revelation is all there. The entire mountain ascent is in and of itself an allegory for Madeline’s journey as a transgender woman, to all of her thoughts internally fighting her every step of the way, getting stuck in the same place only to eventually make progress when she had kept trying enough times, to finally reaching the top of the summit and experiencing that feeling of clarity. The game’s lead programmer, Maddy Thorson, is herself a transgender woman, coming out and announcing as such a year after the game was made. Perhaps she had built the game around her own feelings and hardships of discovering her gender identity without even knowing it? The game’s composer, Lena Raine, also happens to be trans.

But the beautiful thing about all of Celeste’s themes is that you don’t need to be transgender to relate to Madeline and her struggles. I’m about as cis as cis can be, and I still found myself viewing and understanding Madeline’s frustrations and the hardships she goes through during the story, though given that I fly my own pride flag every June, perhaps I’m not all that far removed from the game's perceived "queer" undertones after all. No matter who you are, we’ve all had to climb our own mountain at some point. We’ve all had to deal with our Badeline following us around, trying to keep us “safe” by limiting our potential. We’ve all experienced the haunting feelings of believing that we’ve made so much progress, only to plummet downwards, and need to work our way back up. We’ve all needed to confront our negative feelings that are surrounding all of us to finally overcome them.

Just like climbing a real mountain, climbing the mountain that’s inside all of us is never easy, but the only thing we can do is keep going until we reach the summit. I wouldn’t say Celeste is a game about being transgender as much as it is about just being human. Regardless of who we are and the way our personalities make ourselves into who we are, we’re all relatable to each other because we’re humans with human problems that make us… humans. Because of that, everyone can relate to Madeline, no matter how far removed from her identity they might appear to be on the surface.

Pixel Perfection (In More Ways Than One)

If I had a nickel for every video game I’ve played that used mountain climbing to represent one’s transgender journey, I would have two nickels. Which isn’t a lot, but it’s weird that it happened twice.

What I haven’t talked about yet is the atmosphere of the game, and there is a lot to unravel there. Most of the game takes place on snowscapes, so snow level lovers have a lot to like here. This may sound like the visuals would become monotonous after a while, and while most of the game is fairly dark, every level in the game feels like its own fully defined thing. My favorite level in the game, visually, is the underground cave up above. Not only is it by far the most visually distinct level in the game, but all the colors really come alive, and the shading on the pixel art gives off so much depth. I would say the game in general is very pretty to look at.

The game’s soundtrack is absolutely wonderful. Lena Raine did a fantastic job at conveying the feeling of the landscape and all the emotions that the player (and Madeline) will be going through. It knows when to play a light, cheery tune to ease you into the game and when to get a bit more intense when shit gets real. I bought the soundtrack for the game, and I don’t regret it in the slightest. The B and C-side levels come with some really nice remixes too.

Celeste is a great game that’s not for everyone. Given that this is the second positive review I’ve made for a game known to be extremely difficult, I guess there’s a part of me that likes difficult games? I do willingly go out of my way to get gold trophies on every Gran Turismo test, so maybe I am a bit of a gaming masochist after all. It’s an extremely difficult game, which will innately turn some people off, but it works perfectly as a “baby’s first precision platformer” due to the number of accessibility options.

It’s also a very popular game for speedrunners, not only because it’s proof that they can master everything in the game perfectly (because that’s what all speedrunners do), but because all the speedrunning tech that normally is present in games by accident, is in Celeste on purpose. You don’t need to be a speedrunner or even a precision platformer pro to beat the game (I’m living, breathing proof of that), but the appeal here is that everything in the game is a genuine trick that you can master to make your life a lot easier. If it’s possible to do something in the game, you did it in one intended way.

Celeste has a long-lasting legacy ahead of it. Last year, the developers even made a short 3D game called Celeste 64: Fragments of the Mountain. I have yet to actually play it, but it goes to show how much Celeste still remains in the hearts of gamers years later. If you’re a fan of platformers, even if you’re not much for super hard games, Celeste is a game worth checking out. People who are more interested in something story driven with a deep narrative will find a lot in the game worth appreciating.

Celeste can be purchased on either Steam, Epic Games, Nintendo Switch, PlayStation 4, and Xbox. The Steam version also gives you the added bonus of being able to buy the soundtrack.

Comments

This game is astoundingly good and I highly recommend everyone give it a try.